Keep ahead of the threat

Stay up to date with the latest mycotoxin information by signing up to our newsletter

The heightened risk of Penicillium mycotoxins in European forages

Author: Dr. Max Hawkins, Global Technical Support Manager, Mycotoxin Management, Alltech

Ongoing assessment of forage samples across our Alltech 37+® lab network allows us to build a comprehensive picture of variations in mycotoxin contamination patterns and how these patterns can change over time. One of the main insights that the data have revealed in recent months is the contrast in the types of mycotoxins present in forage-based diets tested in Europe and the U.S. When assessing the risk in total mixed rations (TMRs) destined for dairy animals, there is a notable difference between North America and the EU in the types of mycotoxins that pose the greatest risk to the cow. In North America, the overall risk equivalent quantity (REQ) is more greatly influenced by Fusarium produced mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol, fusarenon X, T-2, HT-2, fusaric acid, and zearalenone. These are potent mycotoxins that can significantly impact cow performance and health. Although these mycotoxins are present in European TMRs, they are typically less prevalent, occurring at lower risk levels. Across Europe, testing continually reveals that the greatest mycotoxin risk is coming from the Penicillium group of mycotoxins, such as penicillic acid, roquefortine C, and patulin.

Why the contrast between Europe and the U.S.?

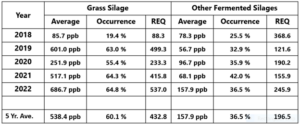

Although the reasons for this contrast in mycotoxin occurrence are likely multifaceted, one of the main contributing factors is probably the types of forages used in dairy diets. In the U.S., corn silage is the major forage component in TMRs, while in Europe this would be grass silage. Even within Europe, there is a notable difference between the types of mycotoxins that are present in grass silage and those present in other fermented forages. As demonstrated in Table 1, an analysis of mycotoxin test results from the past five years in Europe shows higher levels and occurrence of Penicillium mycotoxins as well as a higher REQ for dairy cows in grass silage versus other fermented silages.

Table 1. Five-year averages for Penicilliums, occurrence and REQ in grass silage and other fermented silages

Should we be concerned about Penicillium mycotoxins in dairy diets?

When present in dairy feedstuffs, the Penicillium group of toxins can significantly undermine cow health and performance, leading to:

- Decreased dry matter intake (DMI)

- Lower milk production

- Altered milk components

- Disruption to the rumen microbiome

- Gut wall damage

- Compromised liver function

- Lowered immune response, including higher somatic cell count (SCC) and more mastitis issues

Managing the forage storage period

Penicilliums are often referred to as “storage mycotoxins” as they can increase rapidly during storage and feed out. However, it is likely that the Penicillium mold Penicillium roqueforti arrives at the storage facility with the freshly harvested grass silage. The subsequent potential increase in Penicillium mycotoxins can be associated with many factors. Penicillium roqueforti is aerobic but requires very little oxygen to flourish. Therefore, delayed silage filling, poor packing and improper face management at feed out can all result in excess oxygen penetration and lead to an increased presence of this unwanted mold. As with all silages, a quick and thorough fermentation is needed to enhance silage stability. Lowering pH quickly using lactic acid bacteria on a high-sugar forage such as grass silage may lead to the desired pH level. Silage inoculants such as Egalis®, from Alltech, can be of value in speeding up fermentation and reducing the time and resources that Penicillium molds have to proliferate during the initial fermentation phase.

However, inconsistencies in silage management within a clamp can lead to variable levels of molds, and therefore mycotoxins. The upper portion, or crust, and the sides, near clamp or bunker walls, may well run higher for these types of mycotoxins. These parts may be sorted out at feed out to lower risk, but if mycotoxins are uniformly distributed throughout the forage clamp, sorting prior to feeding becomes more difficult.

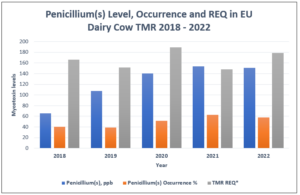

The contribution of grass silages in diet composition will be a determining factor in the Penicillium level in the final TMR delivered to the animal. The Penicillium levels from Table 1 range from 85.7 ppb to 686.7 ppb, with a five-year average of 538.4 ppb, while Figure 1 below shows the average level of Penicillium mycotoxin in TMRs at 65.4 ppb to 150.7 ppb for a weighted average over the five-year period of 123.4 ppb. Alltech’s guidelines for dairy cows indicate this as a moderate risk level for Penicillium mycotoxins. This level of Penicilliums, along with multiple mycotoxins at a lower risk level, generated a higher-risk REQ for dairy cows over the five-year period.

Figure 1. Average Penicillium mycotoxin levels, occurrence and REQ for EU TMRs, analyzed 2018–2022.

A Penicillium challenge on a dairy farm in Northern Ireland

The Alltech InTouch nutrition team in Northern Ireland has been at the coalface of dealing with the challenges associated with Penicillium toxins in recent years. On one particular farm, 135 Holstein cows experienced a sudden drop in milk and a decrease in butterfat, with fertility challenges also manifesting in the herd. Working with the farmer, the InTouch nutritionist considered a number of potential causes and soon recognized that changes in animal health and performance coincided with the move to a new clamp of silage. Although on visual inspection this grass silage was thought to be some of the best ever produced on this farm, an Alltech 37+® mycotoxin analysis discovered that Penicillium levels were five times higher than normal. A proper mycotoxin control program was initiated to manage the forages and final TMR. With the addition of an Alltech mycotoxin adsorbent to the diet, the cows quickly began to respond, with a reduction in swollen hocks and improvements in rumination, milk production and butterfat levels. Also, conception rates started to rise again. The herd has now returned to an average of 12,000 litres, with 4.15% butterfat and 3.25% protein, and both the nutritionist and the farmer are keeping a close watch to ensure that similar problems can be proactively addressed in the future.

To learn more about managing the mycotoxin challenge in your herd, visit www.knowmycotoxins.com